Everyone wants the next big franchise. Marvel Studios has generated close to $25 billion at the global box office alone since 2008’s Iron Man — and that doesn’t include ancillary revenue, Disney+ subscriptions activated, theme park visits, or games licensing opportunities. Joker, a darker take on DC Comics’ most infamous villain, saw more than $1 billion at the box office and spurred a sequel, with director Todd Phillips in talks to potentially help architect the future of the DC Cinematic Universe.

Star Wars, The Witcher, Sonic the Hedgehog, Pokémon, Harry Potter, The Lord of the Rings, Game of Thrones — even NCIS and Ru Paul’s Drag Race. All of these are franchises that are core to a network or studio’s development plans, core to their expansion efforts and, for many companies that now operate alongside or within a streaming service, the catnip to bring in and retain subscribers.

The term franchise gets thrown around a lot these days, but like any term that gets tossed around, it loses some of its meaning with every new use iteration. What is a franchise? A franchise is a shared universe that features characters, occupations, or settings that overlap and maintain connective tissue via multi-platform and multi-delivery content. For the purpose of this issue, let’s focus on television franchise building for streaming platforms: how that can help larger cinematic universes, how it can lead to full blown universes built out on the small screen, and more.

That means The Vampire Diaries and its Originals and Legacies spinoffs, on top of the books, make it a franchise. The same goes for the Dick Wolf universe, which acknowledges that several shows operate within the same fictional world, building in crossovers and distinct character arcs that allow it to flourish as a franchise under his banner. These exist alongside more traditional franchises, those ones dominated by superheroes and droids, but in effect exist to accomplish the same feat, even at vastly different scales.

This issue of Parrot Perspective is all about franchises, answering a few key questions that have arisen over the last few years.

How important are franchises to onboarding new customers for OTT platforms?

How important are franchises to retaining those customers?

How to avoid making franchise pitfall mistakes?

Franchises are important, but they’ve also become terms thrown around to satiate Wall Street without really understanding how to properly use them for customer acquisition, for growth, for retention, and for distribution decision making. The below piece will explore how to recognize signs of a potential franchise, how to best grow across mediums based on early franchise recognition, and traps to avoid when trying to find the next franchise.

Establishing Franchises by Understanding Franchises

Netflix is developing a Stranger Things stage play and a new live-action Stranger Things spinoff with the Duffer Brothers at the helm. Part of this is an attempt to ensure the brand’s longevity is secured beyond the show’s final season set to air in 2023, but it’s also one of Netflix’s strongest attempts into building a franchise.

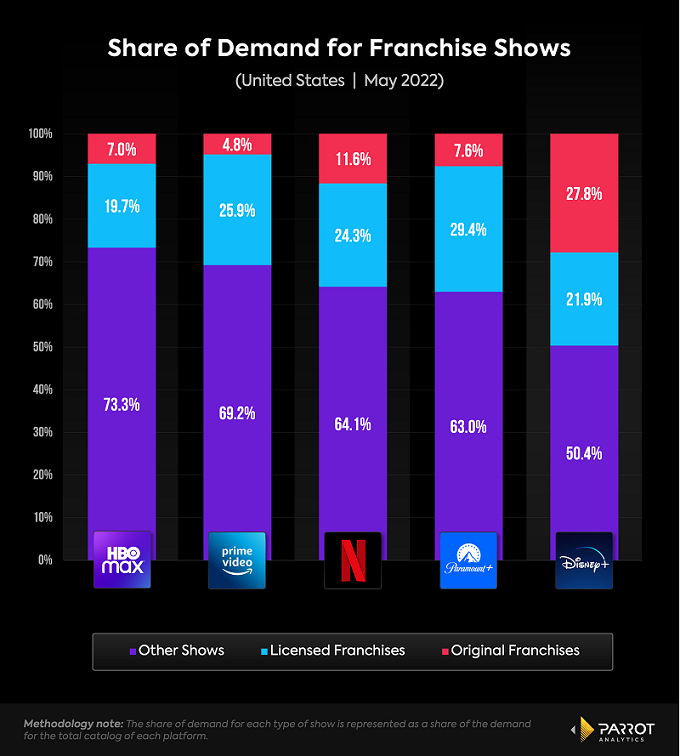

Netflix has the second highest demand for licensed series, exclusive and non-exclusive, according to new analysis conducted by Parrot Analytics. Nearly 40% of demand for all Netflix series in May 2022 was for franchise shows, with 11.6% of that demand coming from exclusive series (like Stranger Things) and 24.3% of the demand coming from non-exclusive franchise series, like Pokémon or Supernatural. This is second only to Disney+, which sees about 50% of total demand for its platform come from franchises. Nearly 28% of that demand is for original franchises, while 21.9% is for non-exclusive franchises.

Disney builds itself around franchises. Its studio divisions practically operate to build out franchises from the get-go. There are plans for sequels if demand is met, and box office sales are high. This coincides with consumer products and theme park divisions working those titles into their lineups, with characters being licensed out to video game developers to continue capitalizing on attention. As Parrot Analytics’ Director of Strategy, Julia Alexander, told Reuters about Netflix and Disney’s franchise approaches, “Do we have the same confidence in the Netflix machine as we do the Disney machine? No, but in part that comes from Disney spending years determining what that machine looks like.

“For all of Netflix’s dominance in the streaming space, they’re still relatively new to building out these types of worlds.”

The word franchise often goes hand-in-hand with the vast majority of Disney’s output. That includes streaming. Comparing the average demand of franchise series to the average demand of non-franchise series nearly doubles in favor of original franchises on Disney+. This is far greater than any other competitor. Before going any further, however, we must determine what equals a franchise and what doesn’t. The chart below goes into more details.

Breaking Down Franchise Standing and Opportunities

Key to Disney+’s expansion plans is expanding beyond franchise to find new, general entertainment programming that appeals to a wider audience. While CEO Bob Chapek and his team still see room for growth within the company’s main franchise pillars, including Marvel and Star Wars, eventually that audience will hit its capacity and the streaming platform will have to scale beyond it.

That means the supply side of the equation has to shift in order to create a new wave of demand for non-franchise series. Although 73.4% of series on Disney+ are non-franchise series, Disney+ still relies on the highest number of franchise titles both on the original and licensed front. Nearly 91% of titles on Netflix are non-franchise series, while 90.5% of titles on Amazon Prime Video are non-franchise titles.

Just as important a data point: the average demand of a Disney’s original franchise shows are nearly 3x the average demand for non-franchise shows available on Disney+. This is one of the largest gaps in favor of franchise shows across the major platforms. Netflix and Amazon Prime Video, for example, show major favoring for non-franchise series. This makes sense when considering that Disney’s main concern with Disney+ programming is expanding the scope of its offering to broaden the overall total addressable market for its subscriber base, and one of Netflix’s biggest issues is finding new franchises outside of Stranger Things.

In Q2, Netflix’s global demand share for streaming originals plummeted from 45.2% in Q1 2022 to 41.2%, another all time low. The last time Netflix’s global share dropped more than this was in Q4 2019, when both Disney+ and Apple TV+ entered the market. The only thing that helped Netflix in Q2 was Stranger Things’ return with its fourth season, which saw 229.6x more demand than the average show worldwide in the days following its May 27th debut. Or, put another way, without Stranger Things, demand share for Netflix originals would be 2.1% lower. Only the final season of Game of Thrones hit a higher peak demand.

In fact, from May 27th, when part one dropped, to June 30th, Stranger Things averaged 193.2x with US audiences — making it 279% more in-demand than the next closest digital original, Amazon’s The Boys (51x). Globally it averaged 200x, 124% ahead of second place The Boys (89.2x). It’s a reminder that building out more franchises like Stranger Things is paramount to Netflix’s continued growth.

Building out the Stranger Things franchise is a must do for Netflix as they aim to stem subscriber bleeding in the quarters to come, yes, but it’s not the only franchise play. Currently, Netflix has a limited track record in creating sustainable franchises. Their attempt at building out La Casa De Papel (Money Heist) has not been successful, with the Korean adaptation failing to replicate the original’s audience, or piggy back off the steady rise in global and US demand for Korean content.

For Disney, it’s a matter of determining what general entertainment programming makes the most sense for the Disney+ platform — instead of Hulu, for example — and can achieve growth goals that may not come from the main franchise series in the next 2-3 years.

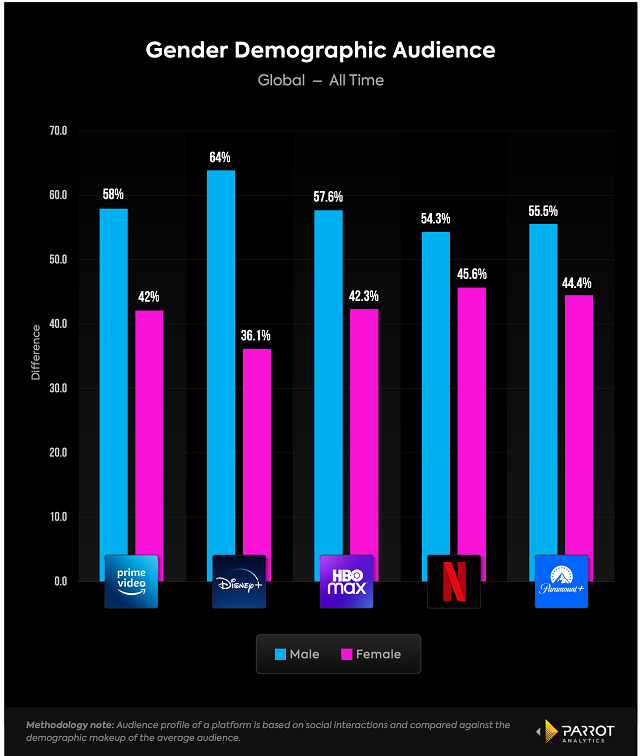

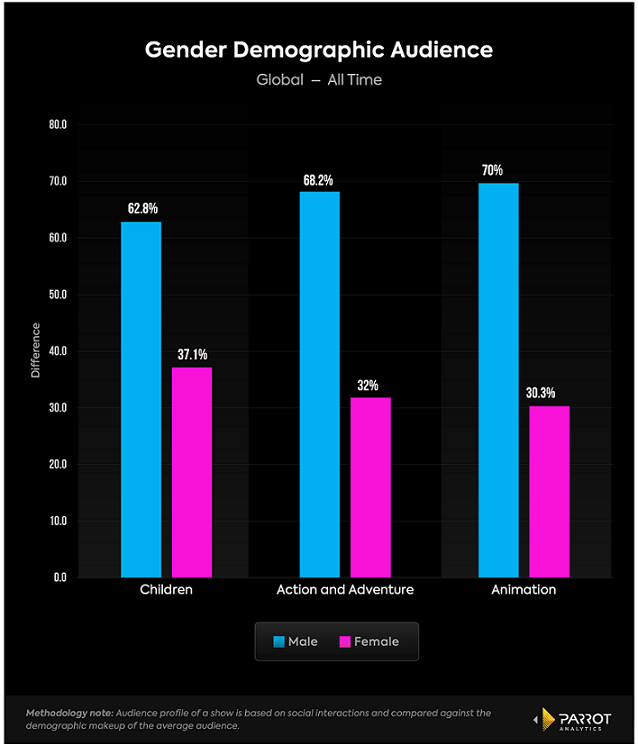

Franchises are key — but the question is whether relying on them too much can lead to hindered growth because of the total audience base and the potential for that audience base to grow. Disney+ maintains the largest demand share for franchise originals in the action genre. This genre tends to lean young and male; while there are attempts to bring in more women (see: Ms Marvel), the best way to grow at scale while not just trying whatever works for the sake of whatever works is to find new general entertainment programming that feels specific to a platform’s identity and can possibly turn into a new franchise that isn’t based around the original audience base.

Building the Base

One of the biggest questions is whether franchises are strong acquisition drivers, strong retention drivers, or a little bit of both? Most high calibre, IP-focused series — especially those based around an in-demand and heavily established film world — are assumed to be high acquisition drivers.

Franchises are necessary to establish the core acquisition base, especially as platforms continue to launch in new territories. Having series that appeal to different audiences within those franchises are also key, like Ms Marvel or The Clone Wars. They are base builders. Understanding the importance of franchises to streaming services comes in three tiers. The first is base builders: a core franchise that acts as a main attraction for a large base of primary subscribers. It is the selling point for a platform, or is the type of show designed to generate a strong surge in subscribers based on pre-awareness, strong affinity, and strong longevity for a title based on IP a company owns.

By looking at the demand for new entries in this type of universe, set against the percentage of demand those titles made up during a particular period (like a quarter), and comparing those to subscriber additions or reductions for the quarter as publicly reported by the company, we can get a better sense of just how integral those titles are to the platform. Similarly, by examining off-peak seasons when there is no new entry in a franchise and comparing that to overall churn the company faced per quarter, we can determine the retention rate of those titles as well.

Each new installment in the Marvel, Star Wars, and DC Universe bring in new customers, but each new season sees a smaller number of subscribers joining in established regions. For example, in UCAN (United States and Canada) where Disney+ has existed for 2.5 years and HBO Max has existed for 2 years, the audience that’s signed up for those services to access their favorite franchises aren’t going to cancel. This leads to smaller groups of acquisitions based on new installments in those franchises.

Therefore, to see scalable growth on those specific platforms, demand share has to come from non-franchise or non-established franchises that reach a group of subscribers in established regions who previously didn’t sign up to Disney+ or HBO Max because the value proposition wasn’t there. Growth stagnates if action isn’t taken otherwise.

Of Disney+’s 10 most in-demands series between January 1st 2022 and July 13th 2022 in the United States, 60% of the titles belong to the Star Wars and Marvel universes. Comparatively, only 30% of HBO Max’s top 10 series in the United States during the same period belonged to well-known action/adventure and fantasy franchises.

While Disney+ and HBO Max saw relatively the same amount of subscriber growth in the UCAN region during the quarter, HBO Max’s base is much more diverse. Therefore, the value proposition of HBO Max to a wider audience as a four-quadrant service is more apparent than Disney+, which is much more heavily reliant on specific franchise installments.

HBO Max and Disney+ see similar skewing in gender demographics for their films, with HBO Max leaning more male and Disney+ leaning more female. They also see similar gender demographics for their television series. But while HBO Max has more consistent offering for people of all age demographics, including Above 40, Disney+ has relatively low demand from Above 40 demographics when it comes to series.

This wouldn’t particularly matter if Disney wasn’t trying to grow its crown jewel streaming platform into a platform that attracted the widest group of subscribers instead of focusing on the primary franchises and core Disney audience — young. To reach the goals set by the executive team for the street, the generational demographic for Disney+ series has to improve, and that’s done by looking for white space opportunities that appeal to a totally different demographic than what’s currently being satiated.

We’ve established that franchises are base builders – a core franchise that acts as a main attraction for a large base of primary subscribers. Disney+ launched with The Mandalorian, HBO Max saw its big rush of subscribers with Wonder Woman and further DC installments alongside the HBO library, and Netflix’s most in-demand series of all time is also its first big franchise — Stranger Things. We’ve also established, however, that base builders can only build so large of a base before the building blocks have to start being added to build beyond the core.

Land and Expand

Think of it like Lego. Once the various pieces start to come together, the potential for those blocks to create something the original designer didn’t even imagine starts to happen much more quickly and at a larger scale. If the first step is base building — laying down the foundation for the Legos to sit on — then base expanders are the various blocks that are used to create something new, tear it down, and do it again.

So, what is a base expander? An expansion of a core franchise that’s designed to widen the TAM not captured by the first base builder. It could be a change in genre, in style, or in medium, but the goal is to double down on the core IP growth while also broadening the perception of what the core product is. If successful, the franchise takes on slightly different identities to different taste clusters, but is all regarded within one main universe.

Let’s use The Vampire Diaries as an example. The original series focused on a female character (Elena) and was effectively an action-romance set within a small town. The show went back-and-forth on her love triangle with the Salvatore brothers. The Vampire Diaries ran for eight seasons. The Originals, a spinoff of the main series, focuses on Klaus Mikaelson. The show is a fantasy drama set within New Orleans pitting vampires against werewolves in a much more politically-heavy show. Klaus was the connecting tissue between both series, but the CW was able to broaden the audience with a new show that acted as a gateway in. It was another building block. Then, they added Legacies, which brought a younger generation to the aging franchise and carried on the overarching story by focusing on Klaus’ child.

Each block is a new Lego square that when added together creates a new portrait. Even more important, those various Lego parts allow for proper franchise development rules to be met: not keeping too much time between installments, reinventing the series for each new generation to make it “theirs,” and following a similar tone and setting to ensure it feels like one cohesive universe. These are just some of the rules that must be followed to ensure successful franchise development, but on a streaming service, they’re also central to expanding and retaining a customer base.

In the case of The Vampire Diaries, The Originals, and Legacies, which also spawned comic book lines and games, we can see the Lego building block idea in action. Although the characters are not necessarily reliant on one another, the shared history and lore can help lend to developing shows around secondary and third-tier characters.

Klaus isn’t a main character in The Vampire Diaries, but his relationship to the show allows him to become the vessel for a different series that targets a slightly different audience while also giving the core audience something to chew on. The Originals may be a reason that someone enters the universe — including signing up for a streaming service — but then it connects back to The Vampire Diaries. Since the settings interlope, this allows for interaction between shows without relying on actors. Similar to the Wizarding World, there is a through line even if the main characters aren’t present.

The result is that as demand for one series grows, so does demand for the others. The chart below shows demand for The Vampire Diaries’ eighth season, The Originals’ fourth season, and Legacies’ first season. We can see demand spike for all three, which is the end goal for franchise development, and is a strong signal point for potential streaming growth and retention. Each new series brings in a slightly different audience, and can work to retain the core audience built in from the base series.

The Vampire Diaries may not come across as much of a franchise as the Marvel Cinematic Studio, but the end goal is the same. Finding new ways in for various audiences, especially on streaming services where new content is key and building recognizable universes is more important than ever, having a world like The Vampire Diaries can help with the bottom line.

So what does that look like at other platforms? Take Netflix as an example. Zack Snyder’s Army of the Dead uses the same methodology. It started as a film — Army of the Dead — and was quickly followed by a prequel, Army of Thieves. When Army of Thieves was released just six months after Army of the Dead was released, the original film saw a spike in demand. We can make an estimated guess that Army of the Dead subscribers either returned for Army of Thieves or were consistent Netflix subscribers. We can also imagine these were relatively the same group of subscribers. The demographics are very similar, even if one is more comedic and the other is much more of a typical action film.

The next installment is an anime series spinoff. For Netflix, where anime is a large investment, having an original series that continues to build on the franchise but potentially brings in a slightly different audience expands the total addressable market and creates a new favorite franchise home for a specific taste cluster. This increases the value of those titles because they manage to bring in subscribers, but can keep retention high. As the world expands, so does the necessity to have Netflix in order to experience new installments in the universe.

An essential aspect of franchise building is crossing different mediums to build out gateways. Army of the Dead is a movie. Same with Army of Thieves. The anime series is a TV show. There’s a good chance that Netflix explores a game based on the series for a new batch of audiences to enter the franchise through. Then there are live experiences and other ancillary paths. The idea is to have the franchise remain top of mind via any platform and medium necessary while the Lego blocks continue to build.

Lego blocks also help with the last part of franchise building within the television universe: base expanders. These are titles like CSI: Miami or Law and Order: Organized Crime. They’re defined as a new installment that plays upon a familiar, recognized formula but creates a feeling of freshness that brings a sense of new to the franchise to keep fans engaged.

The attention economy requires consistency on behalf of the content provider and adoration, affinity, and demand from the consumer. To keep a franchise top of mind, this includes finding ways to keep the audience’s attention and demand. This isn’t an expander play to broaden the audience, but a play to keep a franchise top of mind. These are integral to television; there’s a reason that NBC, ABC, and CBS have employed this tactic for years. As streaming starts to build out its own catalog and library, finding shows to expand in without having to worry about attracting a whole new audience — these are retention and brand admiration plays — will also become important.

Now, building franchises? Easier said than done. Building franchises is exceptionally difficult — just ask Netflix. Just as important to trying to get the process right is actively recognizing mistakes and pitfalls to avoid.

Don’t Repeat the Same Mistakes

One of the most important films Disney released in its recent tenure is John Carter. The 2012 film is most remembered for being a colossal box office failure. The film. which cost $300 million to make, amassed less than $250 million domestically, with $less than $75 million at the domestic box office. It was also, however, a perfect example of how approaching a franchise starter the wrong way can have catastrophic results.

John Carter’s failure felt like it came from, in part, Disney executives believing that they could manufacture a franchise simply because it was a) some form of IP and b) Disney needed franchises, as our director of strategy previously pointed out. The Disney franchise machine wasn’t as well-oiled in the early 2010s as it is today. Many of the franchise attempts were blockbuster failures. Disney, a company known best today for its ability to generate strong adoration for its collection of big franchise titles, couldn’t figure out how to get audiences to love their live-action products.

John Carter was created as a film that might work because it kind-of-sort-of looked like one that should work, and if it kind-of-sort-of looked like the type of film that led to major successes (X-Men, Batman, Pirates of the Caribbean), then maybe it could work as a franchise for Disney. A $200 million loss later, and that plan was no longer the case. Disney’s fix was one of acquisitions. The company bought Marvel Studios and Lucasfilm and, through producers like Kevin Feige, Jon Favreau, Dave Filoni, and Kathleen Kennedy, created the most successful franchises to date.

So what are the pitfalls?

Over-indulging, under-planning

Assuming, not watching

Overestimating structure, undervaluing writing

Let’s break this down further. The first point is in line with the aforementioned budgets. Netflix spent $200 million on Jupiter’s Legacy believing it could be the company’s answer to Marvel and DC. Netflix wanted a superhero franchise. Other, non-Marvel or non-DC owning companies like Amazon found success with The Boys. Netflix spent $50 million on acquiring acclaimed comic book writer Mark Millar’s production company, MillarWorld, to place that bet.

Now, this isn’t to say Netflix went in without any creative development strategy. Of course the teams did. No one sets out to make a project people aren’t interested in. But Netflix over-indulged on a concept instead of letting the first season play out for a fraction of the cost and planning out different case scenarios to move the franchise forward.

Millar is moving forward with other projects that he has at Netflix, but Jupiter’s Legacy was supposed to be the big kickstarter. Instead, it became an overpriced example of what not to do. The show peaked at 24.5x the average demand of all series globally, which is decent, but within a month was hovering around 7x the average demand of all series globally, putting it in the average category. It’s an expensive bet for an entire franchise, without much wiggle room to pivot out of successfully to keep the franchise attempt going.

Sometimes a show lands. Sometimes it doesn’t. But franchise development is contingent on having a plan ready. The MCU was already set in motion with Iron Man when Samuel L. Jackson’s Nick Fury appeared. It was continued in The Incredible Hulk and Captain America: The First Avenger, but if Iron Man failed spectacularly into The Incredible Hulk, the team could have pivoted to trying a new way in without having wasted hundreds of millions of dollars. Planning is essential, but don’t bet everything on the first go.

The second point — assuming, not watching — is what’s happening with franchises in general. At the beginning of this piece, I noted that everyone wants a franchise, but they’ve also become terms thrown around to satiate Wall Street without really understanding how to properly use them. When Netflix or Amazon want a franchise, it’s a Marvel or a Star Wars or a Harry Potter. It’s precisely what executives at Netflix told Reuters just before the company announced its second quarter earnings.

There’s an assumption, therefore, that because one thing worked, another will also work. A great example is the Fantastic Beasts films. Since the original Harry Potter films worked, the theory was that something set within the Wizarding World would as well. A clunky story matched with trying to make five films out of a two-film story arc meant that demand decreased with each new installment and box office return also diminished. While the demand peak for The Secrets of Dumbledore is higher, demand tapers off faster than it did for The Crime of Grindelwald. More importantly, it didn’t do anything to move the franchise forward in any meaningful way.

Diminished financial gains are one key component of the story, and are necessary to understanding expansion or contraction efforts, but franchises are dependent on adoration, which is harder to quantify. Demand and sentiment, which Parrot Analytics tracks, is one way of doing so. If sentiment is high through multiple different expansions, the chance of a more successful franchise development strategy is also higher.

By watching what’s working well for other franchises across different mediums and in non-theatrical expansions, instead of just assuming that something will work because it belongs to an established IP or because it has ties to an established IP genre’s, will help understand what audiences want. How does demand for certain shows, and sentiment for certain trends, help with developing a franchise strategy plan? This is essential to ignoring missteps that others have taken — mainly assuming that just because the audience is there once means they’ll always show up if there’s a brand attached.

Franchises are interlocking stories that create enough widespread adoration and demand that ancillary paths become viable gateways and continuations to create a meaningful flywheel model. None of this works if the storytelling is bad.

That’s the last point — overestimating structure, undervaluing writing. A franchise only works because there’s consistent investment in the next story from the fanbase, and that comes from trust that the stories will continue to bring them joy. It’s why concerns over sentiment regarding Marvel Studios’ recent CinemaScore ratings bring up questions about quality potentially diminishing as supply of content ramps up.

Data and structure is a lighthouse. It can shine a light on opportunistic paths that were maybe invisible before, and it can direct away from treacherous paths. But the lighthouse exists to give the ship’s captain a clear runway to do what they do best — steer the ship safely into the harbor to deliver the goods to people in town. That’s so important to keep in mind when developing franchise strategy. Planning, data, and structure are key to building out the world in a lucrative manner, but the creative teams are what drive continued investment.