The concept of asymmetric warfare was first popularized by Andrew J.R. Mack’s 1975 article “Why Big Nations Lose Small Wars”(1). In the article, he explained how a large nation with huge material advantages could lose militarily to a small nation with insignificant resources. By pursuing a strategy unavailable to the larger nation—or simply one it wasn’t familiar with, or wasn’t willing or speedy enough to adapt to—the smaller nation could win against overwhelming odds.

The concept of asymmetric warfare was first popularized by Andrew J.R. Mack’s 1975 article “Why Big Nations Lose Small Wars”(1). In the article, he explained how a large nation with huge material advantages could lose militarily to a small nation with insignificant resources. By pursuing a strategy unavailable to the larger nation—or simply one it wasn’t familiar with, or wasn’t willing or speedy enough to adapt to—the smaller nation could win against overwhelming odds.

It’s a David-vs.-Goliath play that has applications in any competitive environment—one of which, of course, is marketing. Asymmetric marketing involves any strategy in which a smaller company can out-compete larger players by investing modestly in areas in which it has some kind of advantage over those larger players.

ASYMMETRIC MARKETING EXAMPLES GOOD AND BAD

Marketers often think of “earned” media (particularly viral videos) as asymmetric marketing opportunities—they’re cheap and fast, which make them quite easy for smaller brands to exploit. For example, it might cost a few thousand dollars to create a viral video, as compared to a single 30-second primetime ad, which costs $112,000 to run. Most ads need to run several times.

But the power of earned media as an asymmetric strategy is more appearance than reality. Marketers have learned the hard way that creating successful earned media and viral marketing campaigns is hit or miss, and that a company must miss many times in order to score a hit. Each video might be cheap and fast, but the time and money between successes can easily make them expensive and slow. Besides, efforts of this kind don’t really scale: Dialing up this kind of effort with any consistency is virtually impossible.

A better example is the exploitation of data and algorithms. In his bestselling book “Moneyball,” Michael Lewis explains how the general manager of the Oakland Athletics baseball team, Billy Beane, used analytics rather than conventional wisdom to assemble a team competitive with teams such as the New York Yankees, even though the Yankees’ payroll was more than three times the size of Beane’s salary budget. Marketers have embraced the Moneyball concept, investing relatively small sums in data and analytics in search of an edge. Not surprisingly, they’ve had much more success than with viral videos.

A SURPRISINGLY OBVIOUS ASYMMETRIC MARKETING TOOL

But even the kind of marketing advantage you can get through sophisticated analytics won’t get you five percent growth—particularly since all your competitors are playing the same game. Certainly, it will cost you more than $100,000. Opportunities that require sophisticated mathematics aren’t easy to discover.

Sometimes, however, asymmetric opportunities are right in front of our faces—literally. In an odd way, it’s their obviousness that keeps them undiscovered. (One of those asymmetric opportunities is packaging.

PACKAGING AS A MARKETING DRIVER

Yes, that’s right, packaging. Packaging is an underleveraged marketing element for most brands. And it’s a marketing element that every brand must include.

What other marketing element is present in 100% of purchase decisions—besides being the most important marketing element besides the product itself at the point of purchase, the most important point in a purchase journey?

And the great thing about packaging is that it’s “always on.” Once the investment has been made, it’s all dividends for years. Indeed, once a brand design or logo ‘takes,’ its value often increases with age. Think of that 12-oz red can, or those golden arches. This means that the ROI is typically much, much higher than almost any episodic marketing activity. Packaging also reinforces and is reinforced by many other marketing activities—for example, advertising almost always features a brand’s packaging—which further increases packaging’s value.

EXPLORATION – THE KEY TO PACKAGING SUCCESS

Right about now, you are probably thinking, if packaging is such a powerful marketing tool, why don’t marketers think about it more? Or you may be thinking, surely they do think about it enough—how could this not have been explored?

The truth is, they don’t think about it more—of them, anyway. And the reason is that it has been explored. Sort of. Research shows that approximately 90% of new package designs yield no volume impact whatsoever. So most marketers believe that packaging efforts won’t lead to any measurable market success.

It turns out, however, that most packaging makes little difference because the process is based on avoiding risk rather than maximizing the upside. Senior brand managers live in fear of launching a bad design that could hurt them in market. Rather than risk disaster, they play it safe and select designs close to what they already have. Because of this, designers are often hesitant to explore a lot of bold designs, or they cut them out of the process early, because they know the client will inevitably choose safe any way. It’s a vicious cycle that limits the creativity—and profit maximizing—potential of design.

It doesn’t have to be this way. The key is to ask for and enable design exploration—really broad design exploration. The narrowness of most package design efforts is a huge barrier to winning designs. In fact, 50% of packaging agency professionals said that, on average, they present three or fewer designs to clients. Yet, at the same time, 62% of CPG professionals agree that exploring more design directions earlier in the process would help them to identify higher-performing designs.

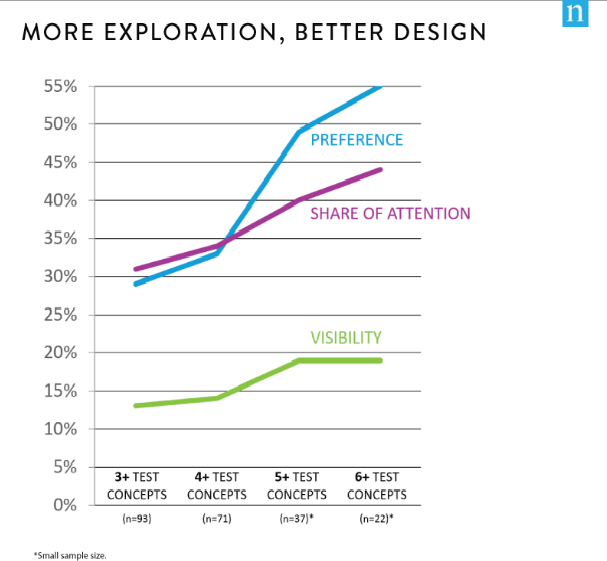

We know that quantity begets quality. Using readily-measured indices of packaging success such as preference, share of attention and visibility(2), Nielsen found that scores increase dramatically as the number of options presented increase.

Don’t be part of the 59% of CPG professionals who feel that too often they stick with what’s safe and don’t consider bolder ideas that might have more potential. It’s simple, really. More package design exploration equals better packaging. And testing for preference, share of attention and visibility is a straightforward way of using objective data to improve subjective decisions.

BETTER PACKAGING, INCREASED SALES

And better packaging means increased sales. Our tests suggest that packaging optimized based on broad exploratory design efforts will generate an average +5.5% forecasted volume lift over the current package design. Combine this with the average $102,000 cost of a package redesign effort, and you get a very, very robust, long-lasting return on your marketing investment.

Marketing isn’t war, thankfully. But just as big nations can lose small wars when faced with asymmetric tactics, as Andrew Mack explained, small packaging investments can win big sales – very big sales.

Written by Randall Beard, President, Global Innovation Nielsen