Immigration may be controversial, but the world would be a poorer place without it.

Immigration may be controversial, but the world would be a poorer place without it.

The world is facing the biggest global refugee crisis since the exodus of 800,000 Vietnamese boat people following the Vietnam War. This has made migration a political hot potato in Europe and in the American presidential election campaign. But much of the fearmongering often drowns out the huge benefits of migration. Economists agree that skilled migrants contribute significantly to growth, job creation, entrepreneurship and innovation. This is why Syrian refugees, many of whom are skilled, are receiving European visas quickly.

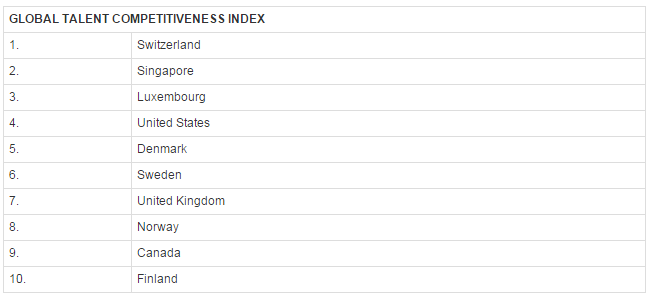

While most migration is from developing countries to rich ones and is often met with hostility, it has played a major role in the development of over half of the 20 most talent competitive countries in our Global Talent Competitiveness Index (GTCI) 2015-16, among them Switzerland (with 27 percent of its population being foreign born) and Singapore (with 43 percent of its adults from overseas), but also the US, Canada, New Zealand, Australia and Ireland.

While rich countries dominate in attracting the brightest workers, however, the performance of emerging countries, especially the BRICS is not improving. Partly due to the cooling off in the growth of emerging markets, talent competitiveness is suffering. Brazil (67th) has declined, with India (89th) and South Africa (57th) being held back by a lack of vocational education. Russia’s ranking was the same as last year’s (53rd) but its rank on internal and external openness fell significantly.

China (48th), however, performed well on its ability to develop global innovation skills. Indeed multinational corporations are moving more of their R&D and product development centres to China, Vietnam, South Korea and India because innovative talent is there —at a lower cost. While migrants typically go to where jobs are, jobs are increasingly going to where talent is.

“Brain circulation”

Rich countries continue to attract and retain the most foreign talents thanks to strong education systems, higher remuneration and a better quality of life. But our findings this year show that this that is not a one-way flow— a “brain drain” as it used to be called. Countries that lose talent to others are increasingly able to capitalise on their diasporas. The mere fact that talent finds opportunities to grow through multiple experiences, under different latitudes and across sectors represents a new kind of positive game on a global scale. The world is moving away from the “brain gain vs brain drain” conundrum, towards a new paradigm called “brain circulation”.

Emigration brings four benefits to sending countries. First, migrants send home remittances, which can account for as much as 10 percent of GDP in countries such as the Philippines. In fact remittances add up to twice global foreign aid, allowing families in developing countries to invest in the education of their children. Secondly, investments made by diasporas in their countries of origin represent a stable source of capital that is relatively immune to economic cycles. In Armenia, for instance, direct diaspora investment (DDI) accounted for more than 25 percent of foreign direct investment (FDI) between 1998 and 2004. Third, there is a network effect whereby emigrants serve as role models and recruitment channels, providing expertise and advice to those in the home country. Fourth, experienced migrants who return home can bring back the expertise to build entire industries and increase the competitiveness of their home countries. Taiwan for instance, reversed in the 1980’s and 90’s its former “brain drain”, luring Taiwanese talent back from Silicon Valley and contributing to the transformation of Taiwan into a global high-end electronics manufacturer and exporter.

Many of the young “millennials” in their teens and 20’s want to study and work abroad. It is becoming clear that mobility is part of talent development. INSEAD research in this area suggests that international experience builds new perspectives and fosters creative performance, notably the ability to exploit unconventional knowledge and creative ideas. Countries and corporations should, therefore, consider sending talent abroad to acquire these innovative and creative global knowledge skills, which can benefit home countries as well as host ones.

Management practices matter…

Regardless of whether a country is attracting foreign talent or attempting to draw its own citizens back home, pay and lifestyle are not the only elements that matter. We also find that good management practices are attractive to mobile people, and the GTCI report highlights two. The first is whether or not management is professional, rewarding positions based on merit rather than patronage or friendship; and the second is the amount of attention paid to employee development. Professional management practices that take staff development seriously are attractive to talent — and the Nordic countries are an exemplar here.

Internationally oriented Chinese companies are becoming more attractive to the “sea turtles” educated abroad, offering international assignments and rich career paths with professional management. But state-owned sectors still struggle, with the science sector burdened with corruption and top-down priorities set by bureaucrats in Beijing. This is partly why 85 percent of Chinese people who earned their science or engineering doctorates in the US in 2006 were still there in 2011.

If countries such as China, India and Nigeria (around half of African inventors live outside their home country) want to encourage their emigrants to head back home, they need to come to grips with patronage and corruption and start taking management practices more seriously. This is especially important to the millennial generation.

…And so do vocational skills

As we find in this year’s report, the scores of China in global knowledge (26th) is higher than its overall country ranking showing significant improvement on this front. Other Asian countries show similar patterns, such as South Korea, the Philippines and Vietnam.

But developing global knowledge skills shouldn’t come at the expense of vocational skills. Our Global Innovation Index, released earlier this year, shows that the most innovative countries are those that foster a culture of vocational development. Vocationally skilled people can meet the needs of industries for specialised skills, and a strong base of vocational talent will be attractive to returning migrants as well as local or foreign entrepreneurs.

Cities emerging

The GTCI focuses on how national economies compete for talent. In today’s world, however, regions and cities are branding themselves to attract talent – and with it foreign direct investment. Cities in particular are becoming more agile and can focus on branding and quality of life in ways that countries cannot. For that reason, we see global companies typically focusing their talent strategies more so on cities and regions than countries because highly skilled people are often more attracted by exciting cities or regions. Dublin, for example, has built a successful reputation as a technology hub and developed an attractive lifestyle for its professionals. Ireland is now the world’s second biggest software exporter, behind the US.

The impact of technology

Migration has become a source of tension, both for countries receiving and losing talent. While the upwardly mobile benefit from migration, those lower down the social pyramid lack opportunities and the necessary skills to participate. That’s one reason why immigration is such a sensitive issue. And the tensions may get worse in the near future since the advancement of technology is beginning to disrupt labour markets in many fundamental ways. Traditionally, technology has allowed some repetitive, dangerous or low-skill jobs to be performed by machines rather than by people. New technologies, combined with new ways to handle information (e.g. big data) are now making it possible to replace knowledge workers too, with a combination of machines and algorithms. Entire professions (accountants, lawyers, bankers) could be affected. Anticipating such phenomena will be critically important to identify the appropriate talent policies to foster economic growth and competitiveness, especially in the emerging world.

Authored by Paul Evans,Academic Director of the INSEAD Global Talent Competitiveness Index and the Shell Chair of Human Resources and Organisational Development Emeritus at INSEAD.

Source:INSEAD