All the talk about the EU referendum, the Refugee Week (20th – 26th June), the stat mentioned in this year’s WPP BrandZ report that Facebook could be classified as the world’s largest country, and a general assumption that the world is now more global looking than ever, had me thinking about the place of, well, ‘place’ in brands. Does it matter where a brand comes from? Or where its products and goods are produced? How much does provenance play a role in people’s attitudes towards a brand?

All the talk about the EU referendum, the Refugee Week (20th – 26th June), the stat mentioned in this year’s WPP BrandZ report that Facebook could be classified as the world’s largest country, and a general assumption that the world is now more global looking than ever, had me thinking about the place of, well, ‘place’ in brands. Does it matter where a brand comes from? Or where its products and goods are produced? How much does provenance play a role in people’s attitudes towards a brand?

It’s not about where you start

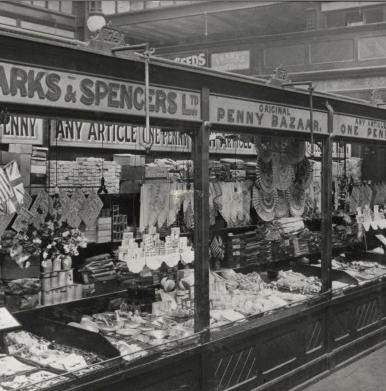

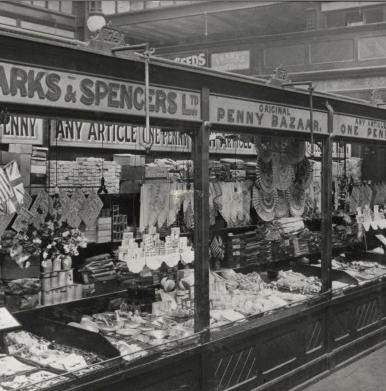

Marks & Spencer is the quintessentially British retailer. Co-founder Michael Marks was actually a Belarusian Jewish refugee who fled the Russian empire to Britain in 1882, starting out selling from a stall in Kirkgate Market, Leeds, before establishing a chain of ‘penny stalls’ across the region. Through his business contacts, he met a cashier named Thomas Spencer, and together they founded the multibillion retailers. Another brand that bleeds Union Jacks is the Mini, but this too was created by, Sir Alec Issigonis, who was a Greek refugee who fled from Turkey in 1922. Launched by the British Motor Corporation in 1959, it is now an iconic symbol of Britain. The growth of both brands has been more fuelled by the places in which they grew, rather than the person behind it.

Or maybe it is

Of course, many brands have been bought up by larger, international companies; Cadbury are owned by American company Mondelez International and Branston pickle is owned by Japanese vinegar maker Mizkan Group. And costs mean that manufacturing hubs have been moved abroad; Twinings is produced in Poland, HP Sauce in the Netherlands and both Lincolnshire sausages and Cheddar cheese can be made anywhere in the world. The fact that these brands and products started out and grew in Britain, and their character is inextricably related to Britain, means that no matter where they are physically produced, the brand remains the same. Brands rely on meaning and being culturally relevant, far more than source.

Origin has value

This year the Great British Food Unit was established, aiming to fuel UK food exports and support industry growth plans, to reach their target of increasing manufactured food exports to £6 billion by 2020. Not only are they aiming to compete with the output of neighbouring France and Germany, but there is a recognised value in ‘Brand Britain.’ Illustrating the power of a country band, a report by CEBR in 2014 concluded that consumers in developing countries were willing to spend an extra 7% on products with the ‘Made in Britain’ label, and from their survey across eight markets, found that at least half of respondents perceived the quality of British goods to be “good” or “very good”. Clarks Shoes has benefitted significantly from their local and British feel. Clarks Village, the outlet store, has become a popular stop for Chinese bus tours. It trades as ‘Clarks England’ in China and has benefitted enormously as a result. It’s the stereotypes of heritage, reliability and quality that make them so attractive. There’s been growing importance attached the value of provenance, and the importance that the story behind where and how a product is grown or produced. Despite only establishing themselves in 2002, Tyrell’s crisps now export 25% of their products, playing on the British humour and heritage to do so.

Are we global or local?

The world’s most valuable brands of course sell across the world. But they haven’t grown just through monopolising markets with generic offerings. Some global brands have successfully gone local. In a term coined as ‘glocalisation’ brands are leveraging the position and financial power that comes from being a global brand, and tailoring their offering for local markets. McDonalds are a hugely successful example of this. They’ve adapted both the products and branding to reflect local tastes, attitudes and values in the 119 countries in which they operate. You can find Gazpacho in Spain, the spicy potato McAloo Tikki and Chicken Maharaja Mac in India, the pitta bread McArabia in the Middle East, and the McLobster in Canada. And PepsiCo faced a barrier with Tropicana in the Turkish market due to the low consumption of packaged juices in the country. Building the brand story and focusing communications that Tropicana sources local fruits and involves local farmers in local regions has helped them build brand equity.

It seems that rather than a particular origin or location being significant, what is most important to consumers is the perceived qualities that the brand conveys in relation to that place. Quality, freshness, personalisation, consistency – these intangible but highly valuable assets that a brand has all matter more than the physical space a product or brand might occupy. Understanding the cultural capital that a place may have, and the cultural context in to which the product from this place is being sold, and using marketing to bridge the gap, means that a brand can be truly global and local.

Source:Added Value